“Symbols can make abstract ideals concrete.”

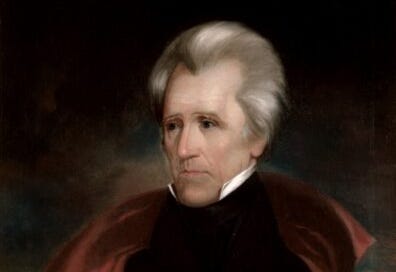

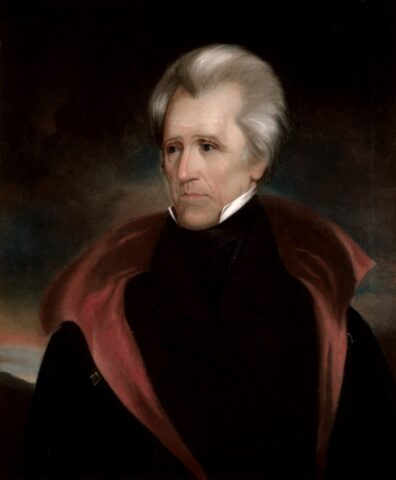

Review of Ward's "Andrew Jackson Symbol for an Age" (

William John Ward, Andrew Jackson: Symbol for an Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955)

Free version here.

One of the best examples of the American Studies school of Myth and Symbol, William Ward’s (1922-1985) Andrew Jackson: Symbol for an Age (1955) is a fascinating study that illustrates a unique perspective on Antebellum America. Fast flowing, this classic became one of the books targeted by the New Political historians of the 1960s and 1970s who vehemently disagreed with Ward’s conclusions. While certainly this book is more of a historical artifact to many scholars instead of a source for scholarship, there were some interesting ideas that could still be useful today.

Ward approaches the Jacksonian years not by looking at Andrew Jackson directly, but rather by seeing Jackson through the eyes of his most loyal supporters and bitterest enemies. Ward argues, as noted by the title of this book, that Jackson is a symbol for the culture and society of early Antebellum America. Consolidating the vast array of 19th century American cultures together, Ward suggests that Jackson was used as symbol for three “structural underpinnings of ideology of the society of early nineteenth century America.”1 These three pillars are the concepts of “Nature, Providence, and Will.” Importantly for Ward, what Jackson did mattered far less than what he symbolized to those around him.

This idea, of a man representing something larger for society is fascinating. Many may scoff at this idea, yet, I wonder how often those who may deride what they may see as pseudo-great-man history may be receptive to modern “symbols.” Barrack Obama represented a great deal of hope to many scholars, with many writing far more optimistically about the future of America during his presidency. In contrast, the 2016 election and the presidency of Donald Trump certainly was seen by many scholars as symbolic of a much larger negative (and to some evil) phenomena in the United States, one that quite frankly prompted a near melt down in many circles in the academy. These two men certainly could be used in the manner of Jackson to portray the age.

In Ward’s arguments Jackson was framed as as farmer, the man of nature, but not a savage. His allies saw Jackson as a man chosen of heaven, but also a man of iron will and self-determination. It does not matter if Jackson was or was not these ideals, what matters to Ward was that Americans thought he was these things. Ward pulls these competing strands of praise together to show how they illustrate broader trends in American culture. These trends, though at times contradictory, were able to be connected together by Americans in constructing a growing and proud American nationalism. Jackson did not develop this nationalism, but rather was the embodiment of it to most Americans (in Ward’s estimation).

For example, the idea of the frontier as a place where true virtue reigned, where men such as Jackson, who were between the “extremes of which are the savagery of unqualified nature and the degeneracy of overdeveloped civilization.” Ward shows how Jackson and his opponents recognized the potency of moving past the Jeffersonian ideal of the power of mind (as embodied in John Quincy Adams) and towards a politics driven by the promptings of a man’s heart (as embodied in Andrew Jackson).2 This trend was also used by Jackson’s opponents, the Whigs, placing William Henry Harrison, their own man from a log cabin, as a candidate for the White House. His victory, in Ward’s argument, illustrates the power of the frontier and the image of the farmer as a man of the people in American culture.

Ward’s work is fascinating, however, his sources have two biases in general. First, they are primarily drawn from elites and upper class sources, thus reflecting a more abstract and at times almost whimsical notion of society. Second, much of his work is drawn from Jackson’s most elite and die-hard supporters. Using these sources is not a problem, however, arguing that this reflected the broader (singular) American culture is overambitious and misses much of the regionalism that was prevalent in (and continues to pervade) American society. If Ward had narrowed his argument to say it reflected a largely elite strata of Jacksonian supporters in American society, the argument likely would have had more merit.

Another challenge with this work is his framing of the Whigs as purely opportunistic elites bent on riding on Jacksonian ideas. The New Political historians clearly showed that it is a myth that the Jacksonian Democrats were the party of the common man. In fact, Jackson’s establishment was as much the party of the elites as the Whigs, if not more so in states such as New York. Ward also fails to really dig into how Jackson also symbolized to many the worst sides of America: slaveholding, brutal treatment of natives, warmongering, disregard of constitutional precedent, and executive overreach. These contra-symbols were as powerful as the more positive images that Ward portrays.3

While there could be much to critique, including the lack of discussion on the brutality in the Jacksonian era against enslaved people and Native Americans, I still found much of value. I am not convinced that Great Man History is entirely worthless (though it absolutely has issues!). Some mortals seem to develop attributes and have a drive that places them in unique situations.4 These people, while not the sole cause of everything in a society, do seem to cause significant changes, for good or ill. Ward’s book illustrates well how some people could see in Jackson an embodiment of what they believed and could see him as an exemplar for their age. Seeing that people saw Jackson in such as light could perhaps help us see some of the good that his supporters viewed that to modern eyes is lost behind the brutality of the Trail of Tears and Jackson’s slaveholding. For some Ward is right in saying that the period was not Jacksons, “he was the age’s.”5

In sum, this was an interesting read which prompted new lines of thinking. A shorter read, there is much to be gained from considering how a man could be used to symbolize the hopes, dreams, and fears of a culture at large.

Robert Swanson

William John Ward, Andrew Jackson, 10.

See Chapter 4.

It should be noted, that Ward is not saying the symbols are good, just that these were what people viewed Jackson as as symbol of.

As a Latter-day Saint, I draw on the idea (for a short video synopsis see here) that prior to this life women and men lived with Father in Heaven (God) as spirit sons and daughters. We developed attributes that, while muted in this life as part of our earthly probation, still are part of who we are. A few scriptures from the Latter-day Saint canon may suffice to illustrate some of the links that I am drawing.

Important to note, that just because a person has strong attributes from the premortal life, does not mean they are forced to be something or do something with those attributes. I am not a determinist. Agency is honored for all of God’s children. We choose, and are influenced by outside factors such as culture, society, and environment, what our character will be and what attributes we develop for good or for ill. Certainly some have developed attributes that made them powerful leaders of men, yet used their gifts for evil. Yet others chose to do good. Regardless, I believe some of the leadership qualities in some people were developed prior to this life.

See end of Chapter 11