Review of Jennifer Morgan's "Laboring Women." (2004)

Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), pgs. 296.

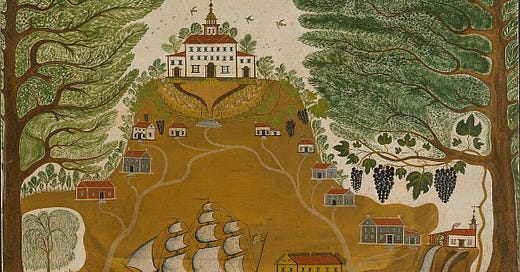

See here.

Laboring Women (2004) is a tragic and fascinating book. Written by Jennifer Morgan, an award winning professor of History at New York University, this book tackles the role of gender in race-making in the early English Atlantic world. Covering a period from the 17th through the early 18th century, Morgan’s work traces Black women’s roles and argues that Black women served not only as an economic asset that enriched English planters, but also served a key role in the creation of race and ideas of the meaning of slavery in the New World. Bringing in a gender focused lens to reintegrate Black women more fully into the story of slavery’s rise and expansion, Morgan weaves together a narrative that challenges ideas regarding the formulation of race and the role of slavery in the Americas in the 17th and early 18th centuries.

Morgan’s work is comprised of six chapters that cover topics ranging geographically from West Africa, to the English Caribbean, to South Carolina and Virginia. Her narrative is strongest when focused on the evidence in Barbados and South Carolina as she musters expansive archival collections from these locations. In re-centering Black women in the narrative of the rise of Atlantic World she importantly shows how white Europeans not commodified and exploited these women’s bodies, but that they viewed Black women as the epitome of what was different between Europeans and people of African descent. Women were the linch pin in numerous arguments in favor of slavery as they were used as evidence of inherent inferiority among people from Africa. At times a bit graphic, Morgan highlights three areas that are key to her central argument of Black women being the center of planters envisioning of slavery.

First, Morgan illustrates that many European writers saw African women as barbaric and perhaps not descended from Mother Eve. Chapter 1 and 2 are the most focused on this theme, though it appears in other chapters throughout the book. In Chapter 1 Morgan details the role of “porno-tropical writing[s]” and the slave trade in creating European ideas of Black sexuality and Black femininity.1 In these narratives English and other European writers develop key stereotypes of Black women as a type of “wild women” or sexually promiscuous, monstrous, and thoroughly suitable to hard labor. These narratives, Morgan argues, were central to how white Europeans conceived Black women and as a whole African culture. Framing African peoples as deviant or even non-human provided the ideological gymnastics necessary to perpetuate the violence and oppression inherent in slavery and slave trading.

Second, Morgan demonstrates that reproduction was a key focus for European enslavers and that planters saw in Black women’s bodies profit through physical labor, but also profit in providing through the birth of children more slaves for the master. This idea undergirds much of Chapters 3, 4, and 5. As she notes in Chapter 3, gender was a “crucial axes around which the organization of enslavement and slave labor in the Americas took place.” She notes that Black women’s capability to give life was seen as an asset, but also an area that Morgan notes was where Black women at times seized control of their bodies through abortions and contraceptives.2 Drawing from plantation records, government records, and other sources, she convincingly illustrates the efforts of planters to control and manipulate Black bodies to obtain greater economic prosperity.

Finally Morgan is emphatic that,

An assumption that all behaviors under slavery were resistant culminates in precisely the same imaginary automaton. For in the vacuum of perpetual resistance, there is no pain, no suffering, no wounds… (Ch. 6)

This concept is especially important, particularly given the context of when Morgan was writing. While she herself does at time seem to favor the idea that much of Black women’s efforts were resistance, she goes farther than most in acknowledging that not everything was resistance. This argumentation can be seen best argued in chapter 6, however, throughout her book she notes that resistance is not always the best way to categorize the actions of Black women. Still today, there is a need to capture a wholistic picture that does not turn all human actions into resistance but instead allows people to have varied and complex motivations behind their actions.

While this book does well at connecting a gendered analysis into this crucial period in the English Atlantic, her work has some flaws. First, while she is far more humble and open to future corrections to her work, there are numerous occasions when she casts blanket statements that fail to show the full reality of the Atlantic world. For example, she argues in Chapter 1 that European ideas of racialized othering stemmed primarily from antiquity (specifically European groups), however this does not leave much room for cultural exchange between slave traders and the slave ship owners. Her narrative also suggests that ideas about people from Africa were uniform across Europe. However, this is not accurate, nor does it capture the seismic shifts in England in the 17th century. Finally, Africa at times feels far too idealized, rather than being portrayed as a place of empires and violence which it, like the rest of the world, was. This further frames Africa through the European imagination, rather than showing Africa for what it truly was, a place similar to the rest of the globe.

Morgan’s book is impressive and does well in integrating gender into a vital topic. While some of the arguments are far too broad and inaccurate, her work on the specifics of Barbados and South Carolina are more convincing. Importantly, her work does accomplish its role in showing the central role of the idea of Black womanhood in constructions of slavery and race.

Robert Swanson

As a Latter-day Saint, this struck me, particularly in regards to modern consumption of pornography. That industry dehumanizes and objectifies women in ways that run parallels to these early travel pamphlets. Morgan argues that these pamphlets helped create a powerful culture that enabled slavery. One cannot help but wonder how the modern industry is impacting the cultural roots of society.

Yet another reason why slavery was one of the darkest stains on American history. It promoted the destruction of families. This is only one of numerous reasons why enslavement cannot be seen in any other light that as an evil institution.