"Must Have had Access": Latter-day Saints and the Movement West of Eastern American Culture.

A review of Robert Winter's "Architecture on the Frontier: The Mormon Experiment." (1974)

Robert Winter, “Architecture on the Frontier: The Mormon Experiment,” Pacific Historical Review 43, no. 1 (Feb. 1974), 50-60.

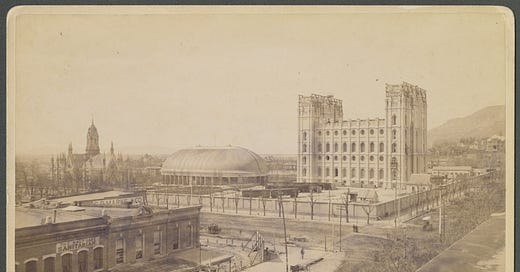

When Robert Winter (1924-2019), an architectural historian and then professor of history at Occidental College, Los Angeles, looked at the structures around Salt Lake City, particularly the Salt Lake Temple, he saw the “projection of an eastern culture.” (60) Writing in a short essay in the Pacific Historical Review, Winter argued that elements of Free Masonry symbolism, eastern United States building movements, and the realities of the West combined into the architectural elements of the Latter-day Saint constructions in Ohio, Illinois, and finally Utah. In sum, different in so many ways from other settlers, Latter-day Saints in Winter’s mind continued the patterns laid out in Eastern architecture in their new western home. Rather than radicals, at least in the way they built their places of worship, Latter-day Saints were conservative and traditional.

This short article is very interesting, particularly when Winter points out how Latter-day Saint buildings fit broadly within other architectural movements then occurring in the United States. This is unsurprising considering that Brigham Young sent Truman Angell to Europe to study Gothic structures in order to better complete designs of the Salt Lake Temple and Latter-day Saints were frequently called to learn from the best sources light and knowledge, including secular sources. Winters does a good job connecting the Kirtland and Nauvoo Temples to Eastern United States trends in mixing classical and Gothic types of architecture, particularly showing how elements of both temples demonstrate ideas then circulating the East Coast. Winters argues that Latter-day Saints never deviated from their roots, but instead sought to build buildings that aligned, for the most part, with Eastern US standards. This article clearly pushes back on the ideas of the West being a laboratory of new ideas but rather an extension of the East.1

However, there were far too many “leaps” in the text where Winter’s stretched his sources and ideas beyond what can reasonably be expected. His sarcastic and mocking jabs that occasionally surfaced were also bothersome as well. One example of the stretching of his sources is when he states

The appearance of ‘conflicting’ styles in the Kirtland temple may, therefore, partially be explained by the knowledge of earlier buildings. Many of the Saints seem to have been well grounded in the art of building and could be expected to be sensitive to novel touches. (53)

While on the surface this statement may not seem all that problematic, the chief challenge of Professor Winter’s foray into Latter-day Saint history is that in his readings is he does not share or seem to know who worked on Latter-day Saint buildings, who directed the construction, or who were the primary builders. Furthermore, a survey of the interior of the two temples would suggest to Winter that these clearly are not inline with other Protestant denominations (a baptistry on Twelve oxen is one of many differences). In one of his sarcastic statements Winter’s writes:

Perhaps these unusual forms may be attributed to divine intervention, for God was constantly advising His servants, Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, on architectural matters, sometimes suggesting the exact measurements for the temples erected in His name. yet, if we look carefully at these buildings, we are less impressed by examples of heavenly whimsy than we are by the Creator’s all-embracing knowledge of then current standards of Western civilization. (pg. 52)

While scholars may certainly debate the role of divine revelation, the key to my disagreement with Winters is his heavy assertions have little in the way of substantive sourcing beyond what he sees on the outside of the buildings (which it should be noted he would be able to enter Kirtland and see drawings of Nauvoo when this was written, as well as see interior photographs of the Salt Lake Temple that had been published earlier in the century). Winter’s offers little more than speculation such as “the Mormon designers may have seen…” (pg. 56) places that were similar to their own constructions without connecting the reader directly from one such similar building and a Latter-day Saint. Ultimately, Winters assertions remain as unproveable as those offered that suggest divine origins.2 While he is correct to note that Latter-day Saints did not cast off their home cultures, he makes little attempt to engage with how the Saints themselves saw or thought about their buildings.

Overall, this was a mostly interesting essay pointing out the influence of the East over the west until the mid-20th century. While some of his points are interesting, this reader would have preferred to see substantially more engagement with primary sources rather than just the authors view of the outside of the buildings. Certainly this is a short essay and offers routes for which scholars to debate in the future, however, even a little more contemporary sourcing would have been helpful.

Robert Swanson

One historian who would argue that the West is shaping the East is Elliot West in what will likely be considered his magnum opus, Continental Reckoning (2021). West in particular avoids discussing the Latter-day Saints in great detail because of how unique they are in the story of the West. See my review here in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (here)

Note I stand by the idea that revelation did occur, however, for scholars, proving this in an academic manner is impossible.