A Razor Thin Line

Thoughts on Doug Hunt's "The Lynching of James T. Scott." (2022)

Thoughts coming after reading: Doug Hunt, “The Lynching of James T. Scott,” Missouri Encyclopedia (2022)

Free digital version here.

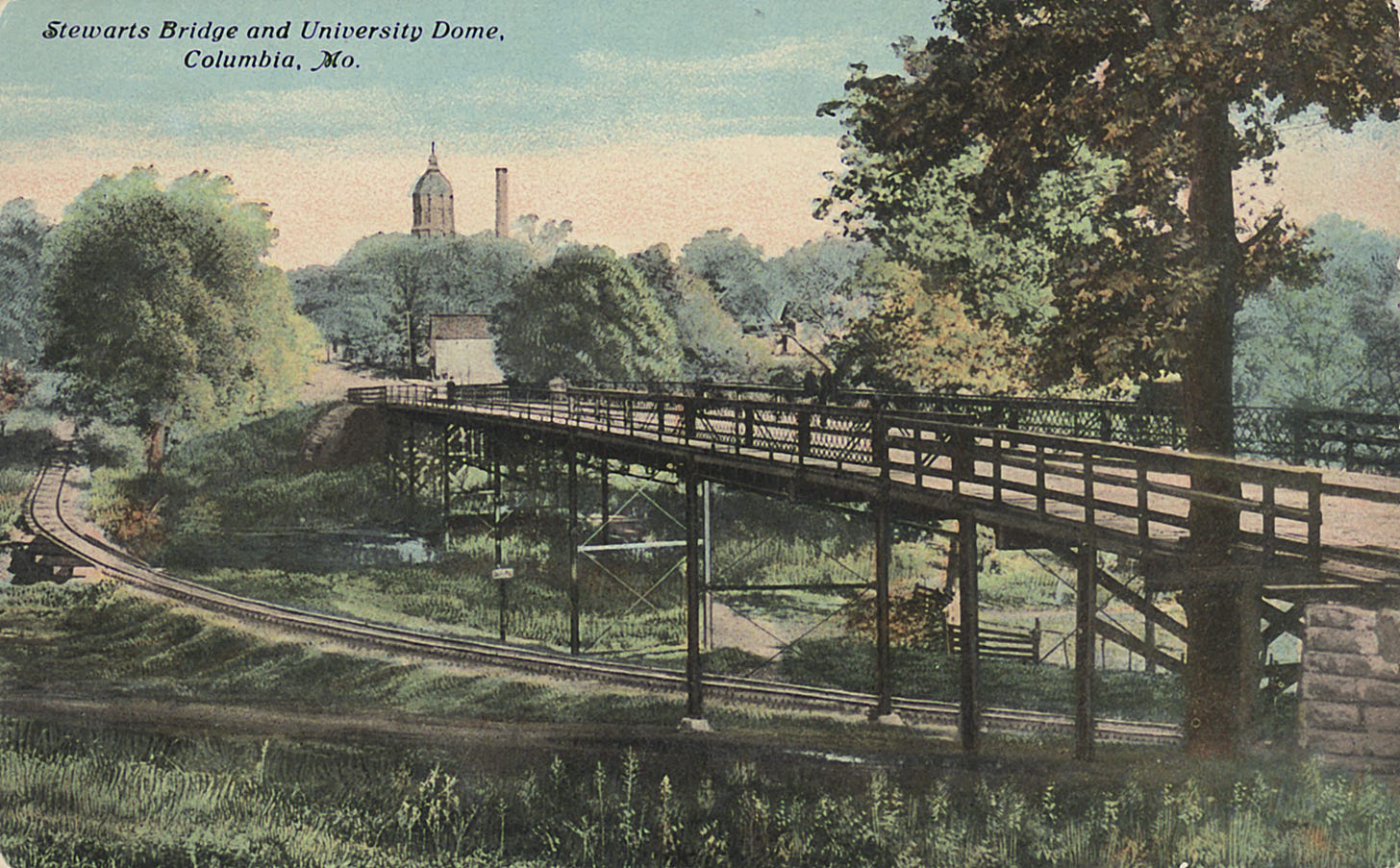

In the spring of 1923, in Columbia, Missouri, a man offered a prayer that surely made the hosts of heaven weep. James T. Scott, a Black janitor at the University of Missouri, before his brutal murder at the hands of a lynch mob on the Stewart Bridge, cried out, “Oh, Lord have mercy on an innocent man.” Moments later he was killed.

Doug Hunt, an associate professor emeritus of English at the University of Missouri authored a short, yet provocative narrative of the murder of James T. Scott at the hands of a white mob for the Missouri Encyclopedia. Written in 2022, Hunt’s narrative is well written, concise, and heart-wrenching. He is a masterful story teller, etching into this Missouri Encyclopedia entry the horrors of early 20th century racial violence. His entry raised two strains of thought as I read it, one historiographical and the other spiritual.

First, the historiographical. I will add below my theological thoughts for those interested. Scholars working with the history of race violence in the United States are in a constant battle with the archives. At times the history of these events are obscured, but at other times are preserved in mortifying detail and even celebration. Scholars debate and discuss the delicate art of sharing truth, while avoiding abusing the dead through a graphic retelling of their experiences. Hunt attempts to walk this razor thine line, though at times as he attempts to paint the horrific actions of the mob, one wonders if he could have been less descriptive, without covering up the sins of the past.

As a historian of antislavery and slavery in the United States, I have a deep empathy for what Hunt is trying to accomplish. Hunt seeks to take the reader to Scott’s view, to see the brutality and horror that has so often been euphemized in historical retellings. He seeks to strike at the heart, to push the human soul to reckon with the past, to confront the vivid hatred that led to the murder of an innocent man. Yet, professionally, I do not want to forever etch the specifics of violence. Human suffering should not be hidden, forgotten, nor ignored. The violence Scott experienced should not be trivialized or swept away. But I do not believe that it is good for any soul to relieve in detail the violence of the past.

There are ways to avoid the vivid scenes of violence while emphasizing the reality of human suffering. Historians and writers of the past must take seriously the need to avoid engaging in violent over-descriptions that continue to etch the evil of the past into the minds of the present. In fairness to Hunt, he by and large walks this line. My own dislike of some of his sentences may simply stem from my own distaste for violence and not a reflection of Hunt’s failing to maintain a balance in his narrative.

Overall, Hunt’s short contribution to the Missouri Encyclopedia is valuable and powerful and his writing is excellent. He could have done more to contextualize this event in broader Missouri history or in national lynching culture, and perhaps even pointed to some of the scholarly debates regarding this tragedy and its impact on the broader community (his additional readings section suggests there might be a few divergent views). However, regardless of these shortcomings, this essay is an important, though brief read that offers a glimpse into a world of fear and hatred that I hope will remain forever gone.

Rob Swanson

Below you will find my second series of thoughts, which are theological in nature:

Joseph Smith, the first prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints once queried heaven, “O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place?” This raw prayer has surely been shared by countless others who like Joseph Smith have seen the effects of men and women giving into their basest and most carnal instincts. For Brother Joseph, this cry came as he saw and heard of his people being driven from Missouri in the midst of winter, the abuses and violence perpetuated against them leaving the prophet frustrated, angry, and confused. Like countless others before him, Joseph confronted the question of evil and why mankind seemed so willing to embrace it. James Scott’s came on the Stewart Bridge.

Eighty-four years later, Scott’s death occurred. This cry of “Where art thou” perhaps may be echoed by others reading of Scott’s death. As a Latter-day Saint, my theology has provided some comfort regarding the evils of this world and of that of the past. While I do not have a complete answer for why some evils are allowed to happen, the Latter-day Saint teachings surrounding Jesus Christ are comforting and compelling. I know that Jesus Christ:

…Shall go forth, suffering pains and afflictions and temptations of every kind; and this that the word might be fulfilled which saith he will take upon him the pains and the sicknesses of his people. And he will take upon him death, that he may loose the bands of death which bind his people; and he will take upon him their infirmities, that his bowels may be filled with mercy, according to the flesh, that he may know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities.1

Jesus Christ understands exactly the emotions and pains James Scott faced and every other person who suffers. He, in a way impossible for me to comprehend, walked the path of each individual human, bearing the weight of eternity and the suffering of God’s children, so that He can come with healing in his wings. I subscribe to the belief that in a future day, when a “new heaven and a new earth” arrive, that “God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes, and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.”2 Christ will heal those broken by the evil deeds of their fellow man. Christ will judge in righteousness and justice, offering salvation to all who repent and come unto him.

These beliefs have comforted and sustained me in my work as a historian, helping me see that both the victim and even the perpetrators, can be healed through Christ. Leaving judgement in the hands of Christ, I seek to instead teach the truth, calling evil for what it was and is. But I take comfort knowing that no depth of pain is beyond the reach of the Great Healer. Hunt’s work was vivid and sad, offering me a chance to meditate on my own belief and faith in the redemption of Jesus Christ.

Rob Swanson