Thoughts on John and Kathryn Glynn's "His Sacred Honor" (2006)

Book Thoughts; American Revolution; American History

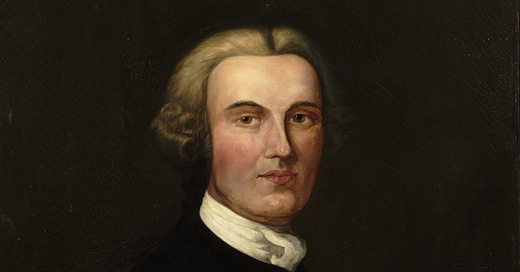

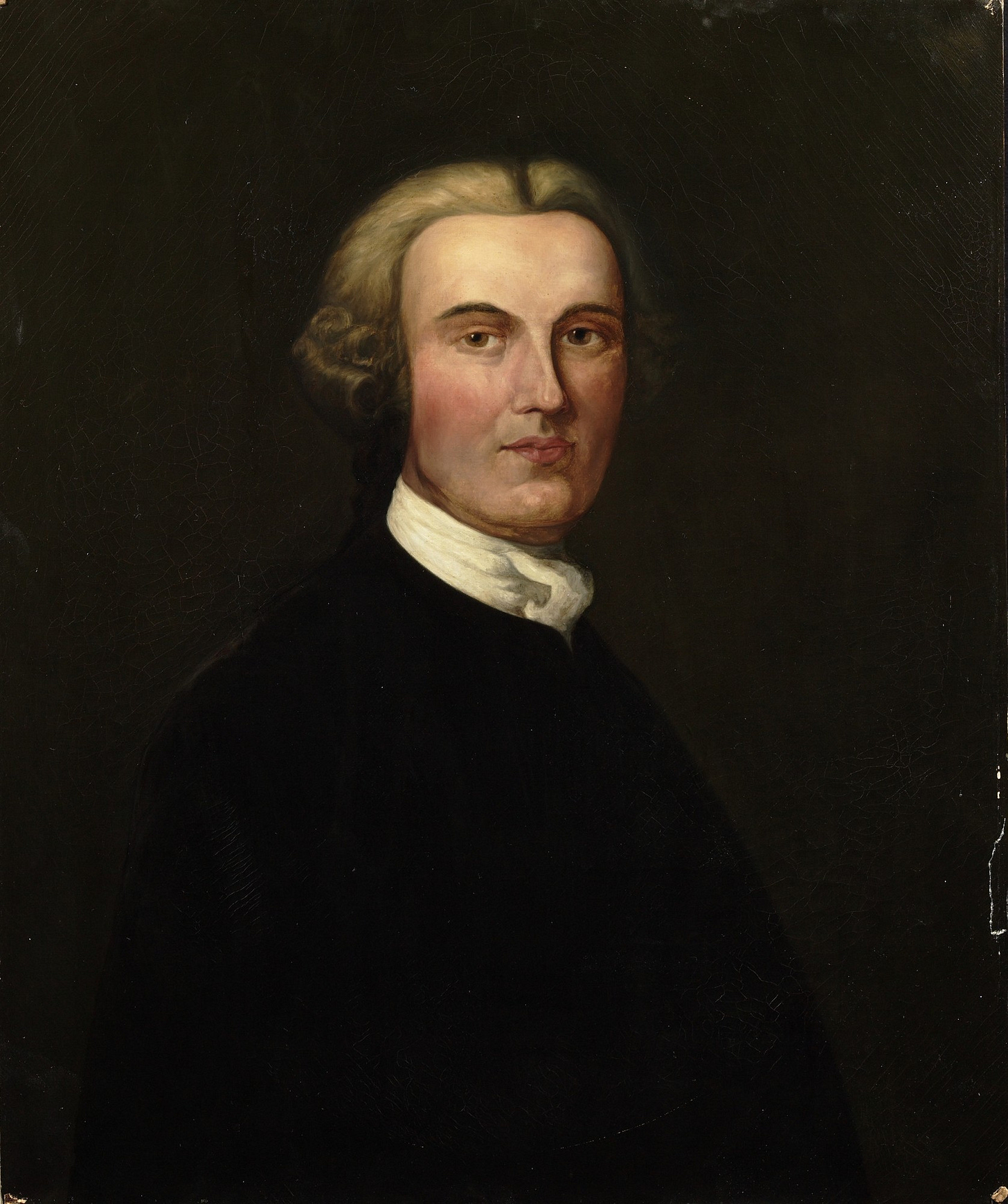

John C. and Kathryn Glynn, His Sacred Honor: Judge Richard Stockton, A Signer of the Declaration of Independence (Brentwood, TN: Hereditea, 2006), pgs. 213.

Returning to books that previously made an impact on you can be a fascinating experience. I first read His Sacred Honor as an undergraduate at Brigham Young University in the Fall of 2017. I was working on a paper for my History 200: Craft of History course and had decided to write about the American Revolution. Through a series of inspired moments, I came across the man known as Richard Stockton. What little I saw written about him indicated that he was a traitor to the American Revolution. I was intrigued. In part because of my faith as a Latter-day Saint I believed the Founders to be honorable men, that despite their imperfections were instruments in God’s hands to establish the United States of America. I felt that as I read the story of Richard Stockton as portrayed by various modern historians, something was off. My first research paper traced the life of Stockton and the cultural influences in his upbringing and I felt strongly that the portrayal of Stockton was incorrect. My search for answers led me to this book, which I first purchased and then read eagerly. Thankfully for my research, I felt that the author had left some holes to fill, but I greatly appreciated the Glynn’s for their efforts and cited the book repeatedly in my first research paper. Though the book played only a small role in my tracing of Stockton’s life, I felt that it exemplified an honest labor and zeal for defending truth.

Six years later, I quickly reread this book and found much to think about. I have a bit more training, now entering a PhD program and having finished my Masters of History. I have read more, researched more, and even presented at an academic conference some ideas I have on Richard Stockton and what his story can tell scholars. It was fascinating to reread this book and explore how I have developed as a historian and scholar in my reactions to this book.

One thing has remained consistent from my first reading to this current perusal. I remain committed to my belief that academics can be wrong in their assertions. Historians can misread or misuse the sources and thereby create a world that is far from the reality of the past. That being said, I think it is less common that scholars intentionally mislead or lie in their works. Rather, I think biases can blind scholars to what they are reading. I certainly believe my work has its biases. Rereading His Sacred Honor reminded me of this skepticism of the academy. The Glynn’s, despite their complete and utter disregard to Chicago style citations (one of the most tragic failings of this book), bring sources that challenge scholarly interpretations of the past. Driven by a zeal to protect their ancestor, interesting stories are retold that complicate the story surrounding Stockton. It was delightful to revisit those sources and the story that the Glynn’s wove. Is the narrative at times inaccurate? Absolutely! But when the text was aligned with the sources, it produced a fascinating story.

A second observation was my amusement at the writing and citations. The work is not in any shape or form an academic text. Though sources are used, the citations are atrocious (something I remember thinking as an undergraduate, but it has only augmented since then) and leave me wondering where I could examine those sources. Part of the tedious citation system of academia is so that scholars can trace arguments back to the original sources. The Glynn’s narrative has the potential to be far more convincing, however the evidence is displayed in a way that can be examined by others. They could learn much from the academy in this regard. That being said, I continue to disagree with other historians on the role of hobby historians. At times there is an air of contempt among professional historians for those outside of the ivory tower that seek to produce history. Rather than see these narratives as useless and even dangerous to the shaping of national discussions, I welcome these works. They provide opportunities for scholars to rethink arguments, to look at the world in a new light. Far too often the academy is entrenched in paradigms, or a singular way at looking at the past. Often, this view or paradigm is broken by outsiders or young members of the profession who relook at the sources and find a new way of viewing the past. I know for myself as I read His Sacred Honor I found some of the ideas intriguing and worthy of future scholarship.

My final observation is the need to return to the sources. I want to recommit myself to studying the journals, letters, diaries, memoirs, and other historical artifacts that tell about the world that is long gone. I want to not go to the past expecting to see things, but rather take it in with fresh eyes, looking to see what conclusions I draw from the sources, rather than looking for validation for the historical arguments that I prefer. While this book was written with the agenda to prove Stockton was a hero, I find that it still has value, if for nothing else it helped me want to revisit the sources of the Revolutionary period in American history and see what wonders I can discover.

I recommend this book to my readers, while noting that there are significant portions that more imaginative than I believe the sources allow. But it does provide numerous direct quotes from primary sources which are a boon to those looking to read transcribed materials from an early American Whig leader in the state of New Jersey.