Greg Olson, “Slave, Trader, Interpreter, and World Traveler: The Remarkable Story of Jeffrey Deroine,” Missouri Historical Review 107, no. 4 (Jul. 2013), 222-230.

Greg Olson, an independent scholar, historian, and a former curator at the Missouri State Historical Society in Jefferson City, Missouri, has published frequently on Missouri’s Indigenous history. I first came across this article as part of a larger work project and was fascinated by it. I believe that this article opens up doors to questioning current paradigms about the broader Atlantic World (though I do not believe this was the author’s intention). Rather than a detailed examination of the merits and weaknesses of Olson’s article, I will focus on one of the paradigms that Olson’s article challenges, which is the role of race in the Atlantic world. (If you would like to read Olson’s article see here.)

Olson details the remarkable life of former enslaved man Jeffrey Deroine. One of the best parts of Olson’s narrative is his allusions to how Deroine’s life story crosses numerous historical fields including Missouri history, Atlantic world history, the history of slavery, the history of law and slavery, and Native Americans in the Midwest, though his primary focus is on Deroine’s neglected role in Missouri history.

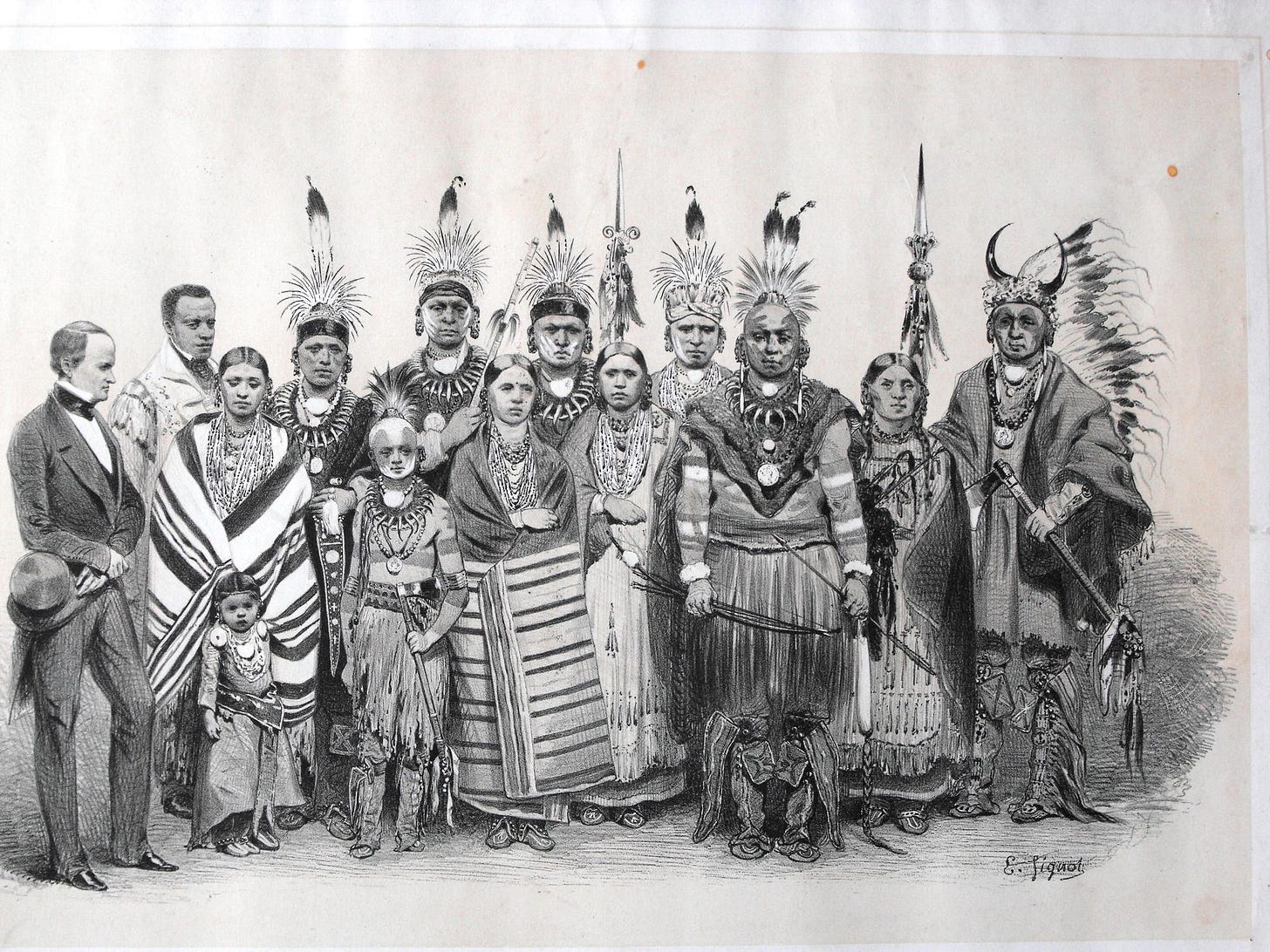

Born to a French-Spanish father and African American mother in what is now Missouri, Deroine moved from being enslaved to become a trader, a United States government agent and translator with the Ioway tribe in Missouri, a translator for the Ioway people’s goodwill tour of Europe to raise funds to help pay down their debts while also raising awareness of the terrible conditions on the government reservation, and was a modest landholder in Missouri.

Many scholars over the past decade have argued that a hard line was created in the Atlantic world between people of color and white Euro-Americans. A “racial modernity” in which skin pigmentation was tied directly to one’s place in the “great chain of being” is argued to have become common place in the Atlantic world by the early 1800s.1 Numerous examples have been used to demonstrate this. However, Deroines ability to easily navigate the Atlantic world and be seen as cosmopolitan, rather that “backwards” or “degraded” suggests that perhaps narratives of racial modernity are not as hard and fast as scholars have suggested.

Deroine’s narrative suggests that older notions of “enviromentalism” or the belief that one was the product of their surroundings, had not fully been killed even as late as the 1840s. The presence of this ideology allowed for a fluidity in which education and cosmopolitaness could lead to a form of integration in society, regardless of race. As noted by Olson, one of the Ioway’s sponsors, George Catlin had few negative or belittling comments about the translator from Missouri (despite repeatedly making such comments about the Ioway). In fact, when Deroine is discussed, Catlin framed him in a similar manner to the cosmopolitan elites around him, rather than the Indigenous people he was aiding. This may come as a surpise to some, particularly when racial modernity was to have created a stark wall between the races where people of African descent could not move beyond a “degraded” social caste. Other evidences not mentioned in the article also suggest challenges to the idea of racial modernity. explain this quote from a newspaper at the time of Deroine’s death:

His interpretation of their languages was so clear and intelligent that he not only made a favorable impression upon all the dignitaries of the foreign courts at which they were received, but, it is said, fascinated a lady of high title -- Disraeli had frequent conversations with him and showed him marked attention ... He spoke French as fluently as he did English, or a dozen Indian tongues with which he was familiar. He was a fine looking man, with a benevolent intelligent countenance, stout figure, modest and respectful demeanor, and was an honest and faithful man.[1]

I am not suggesting that the American Republic or Europe was devoid of racism or that legal and cultural barriers were placed to segregate and demean people not of Western European descent. However, the life of Jeffrey Deroine requires scholars to engage more carefully with a world that was not dominated by a single ideology or theory of race. I particularly enjoy stories such as Deroine’s because they muddle the water, they force me, and I would hope other scholars, to consider the paradigms that we have constructed regarding the past. The force us to consider how much trust we can place in a dominant historical meta-narrative.

The individual and “nitty-gritty” or micro-level individual stories that often get overlooked in the macro-level histories tell a more complicated and nuanced story that given enough attention can reshape the macro in beneficial ways. At the micro-level, a person’s story rarely matches another. Parallels and similarities exist to be certain, but each story contains keys to unlocking a world lost in the mists of the past and to better understand the current complexities of the present and the possible contours of the future.

Robert Swanson