Review of Paul Gilroy's "The Black Atlantic" (1993)

Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), pgs. 261.

Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness is not an easy read. I readily acknowledge my own inadequacies in grappling with theory and philosophy, but Gilroy’s work at times seemed exceptionally difficult, jargony, and theory laden. However, his work, despite its over-complexity, provides useful tools and frameworks for scholars exploring the concept of the Black Atlantic world. Paul Gilroy (1956-present), a sociologist and cultural studies scholar at the University College of London, based this book off a series of lectures he gave while at South Bank Polytechnic in London, England. Largely theoretical with some strong discussions related to Frederick Douglas, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Richard Wright, I will avoid much of the abstract jargon that permeates the work, and instead focus on some key ideas I found useful.

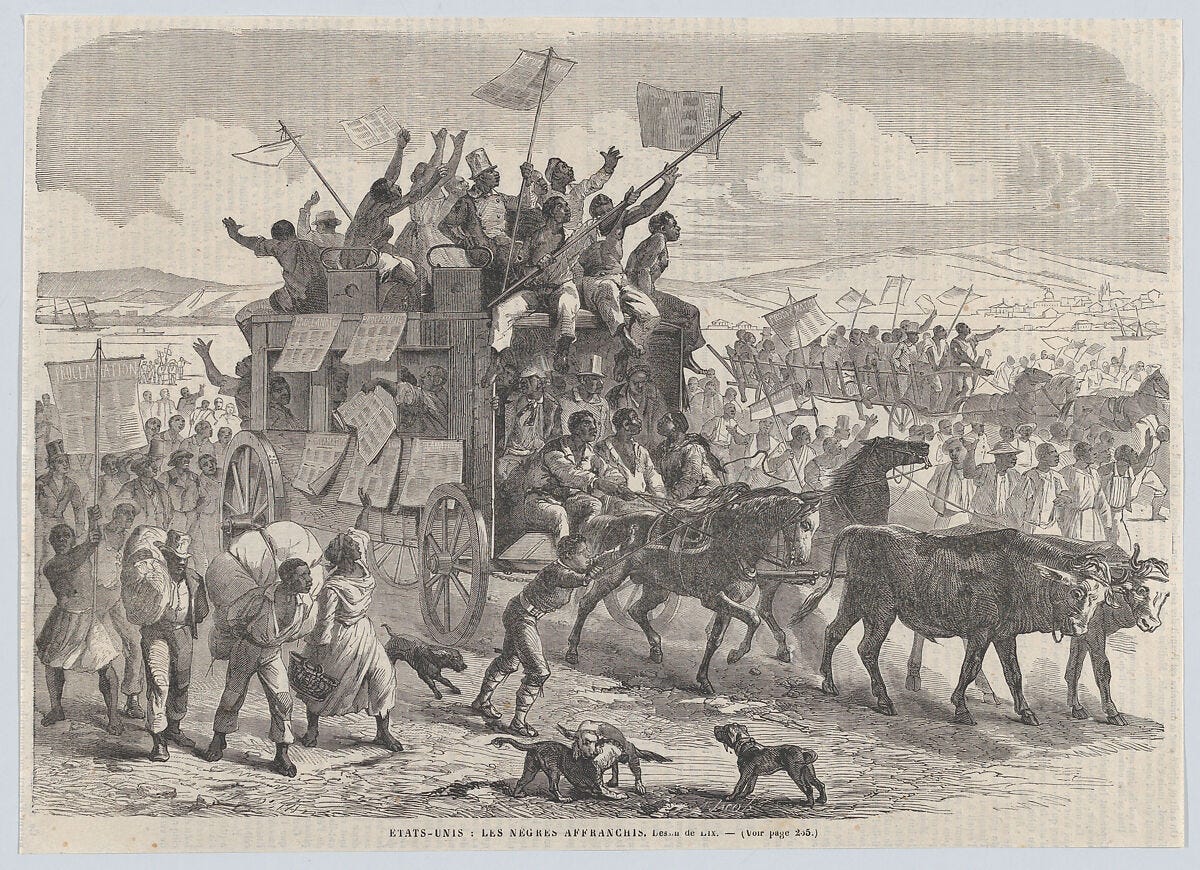

Early in his work Gilroy suggests the idea of “the ships” of the Middle Passage and Pan-African migrations as a “microcosms” of the larger Black Atlantic. On these ships, either carrying enslaved people or colonists, new creole cultures were created and ideas shared that were opposed to modernity. Black intellectuals recognized the power of these ideas and developed them long before post-modernists began their crusade against Enlightenment thought. Thus Black Africans experiences have important parallels across time that are differentiated by the distinctive interactions between white and Black peoples. The role of slavery is central to the Black Atlantic and is one of the core memories uniting peoples across national divides.

This concept of a culture that is both chaotic and divided, but united by its opposition to racial modernity (or subjugation of Black people) and African descended peoples’ coopting of western methods (such as the scientific method) has been hugely influential in current explorations of the Atlantic world. Rather than focus on “nation states,” scholars have begun to look beyond national borders at wider communities that were linked by ideas or experiences. Importantly, Gilroy links the concept of Black Diaspora to the Jewish Diaspora, arguing that there are many shared impulses created out of the fires of suffering. While there is much in this concept that I disagree with, I did find this concept of the Black Atlantic as an chaotic and un-hegemonic culture useful. Too often I feel scholars generalize experience across unique regions in discussing broader human trends, such as the Black Diaspora. Gilroy does this to some extent, but offers the essential caveat of a loosely bound Black Atlantic that still allows for the development of unique Black cultures.

While this book offered a theoretical foundation for exploring the concept of a Black Atlantic world not beholden to nationalistic traditions (i.e. not a static culture, but one that evolves constantly in conjunction with its interactions with other cultures around it), there is much that is tied to abstractions or mythologizing that ultimately ignores Africa and other nodes of the Black Atlantic world such as Latin America. This was a Black-Anglo centric narrative that primarily focused on elites’ perspectives, rather than on the actual lives of the lower sorts making it less useful. Furthermore, Gilroy fails to capture the complex nuances of the passage of time and development of cultures.

Ultimately, this was a complex, at times chaotic, and less fulfilling read. However, its redeeming quality, of pointing to a “chaotic” Black Atlantic makes it a book that can be useful to scholars.

Robert Swanson