James H. Sweet, Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), pg. 320

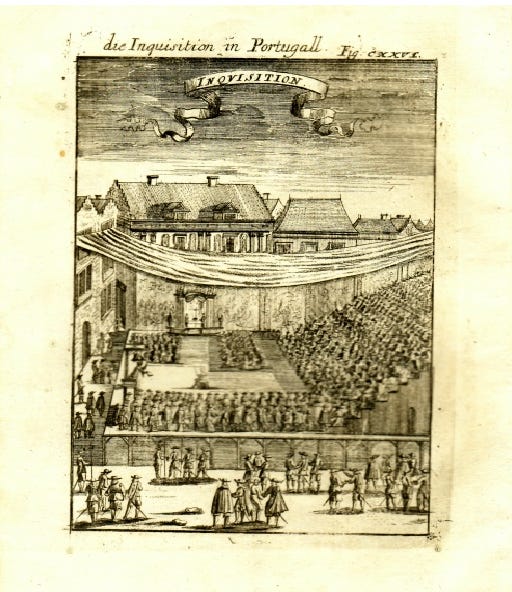

James H. Sweet, a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin - Madison and former president of the American Historical Association (2022-2023), has created a fascinating microhistory studying the life of Domingos Alvares, a African man from an area in modern Benin under the control of the Dahomey. Sweet, tracing Alvares’ narrative through a trove of documents found in the Portuguese Catholic Church’s Inquisition archives, tells the story of a man who traveled across the Atlantic World as a vodun healer and whose story reflects some of the complexities of African peoples in the Atlantic world.

Sweet argues that though Alvares should not be seen through a heroic lens, Alvares’ narrative has important contributions to understanding the Atlantic World as it reflects one African man’s journey in defying the forces of imperialism and capitalism through his practice of healing and community building. Sweet is a powerful story teller and his narrative is well executed. He shows the value of tracing individual narratives in exploring the larger forces at work across the globe in the early 18th century. He offers a more complicated narrative that suggests that on the ground level, slavery was a messy business where white and Black people interacted and participated in cultural exchange. However, there are some glaring issues that reflect larger trends within the academic world.

Sweet explores Alvares’ story across ten chapters, beginning in West Africa, before proceeding to Brazil, then across the Atlantic to Portugal. Sweet has several strengths in this book, which are careful attention to culture and detail, a willingness to accept the messiness of sources, and an openness to complexity in slave societies. One example of Sweet’s attention to detail can be found in the first chapter as he traces the role of Vodun in Alvares’ life. The narrative is fascinating and he demonstrates a careful acknowledgement of the violence and warfare of West Africa. Sweet explores the rise of the Dahomey kingdom and the expulsion of some Vodun priests due to the power they wielded. While I find Sweet overemphasizing the positive nature of Vodun and avoiding any of the darker edges, his narrative is fascinating, particularly as he traces the practice into Brazil. In a world very much still tied to folk magic, it was intriguing to see the range and influence of Alvares on both the Black and white community.

However, there are some areas that reflect modern academic biases. While Vodun receives some theological treatment (that being said, much is missing) the paltry discussions on Catholic theology and the emphasis on tying Catholic actions to secular, rather than religious motivations reflects modern academic biases in attempting to understand religion. This is further played out in Sweet’s constant efforts to reframe what can on the one hand be seen as Alvares’ exploitative, manipulative, and violent actions as “healings,” while Catholic efforts to maintain orthodoxy (which to any priest who believed in Catholic doctrine would have seen Vodun as a threat to their flock’s salvation) are seen as an extension of imperialism. This at times was frustrating.

Furthermore, Sweet did not always clearly delineate when he was taking “imaginative” liberties with the narrative. For example, often Sweet claims Alvares felt a sincere desire to create community. How does he know this? Could not Alvares also be seeking to control and manipulate those under his direction? What documentation exists to prove the charismatic and benevolent character of this healer? The problem with the narrative is not that Sweet chose to frame his subject in such a manner. The problem is that he did not acknowledge the possibilities that could also be extracted from the extant documentation. Readers who do not catch the historians play on words (possibly, perhaps, likely) that indicate a lack of documentation will miss the jumps that the author is making in his arguments.

Sweet wrote a fascinating microhistory of the story of one vodun practitioner in the Atlantic World. His story shows the complexity and messiness of this rapidly changing world, though the author could have gone significantly farther in muddling the waters. Unfortunately, while the author repeatedly warns against hero worship, the narrative he presents is a heroic narrative of resistance. As Sweet says in his final chapter:

As long as Domingos Álvares successfully shined the light of therapy, health, and healing onto the symptoms of Portuguese colonialism and slavery, he offered a competing vision of redemption, a way of addressing isolation and alienation through the prism of a more stable and comprehensible deep past that emphasized communal well-being.

This vision of Alvares is myopic and mythologizing, in some ways part of a larger academic romantic vision of Africa. You cannot expect to find truth when avoiding the uncomfortable realities of human history. The story of mankind is one of both incredible inspiring stories, but also the darkest tragedies. Europeans, though certainly guilty of failings and violence , are not alone in inheriting the effects of a fallen world. What struck me about Alavare’s story is that throughout the narrative the realities of harshness and exploitation are removed to present a heroic anti-western man, the hope of many western academics.

Robert Swanson