Review of Goodman's "Towards a Christian Republic." (1988)

Paul Goodman, Towards a Christian Republic: Antimasonry and the Great Transition in New England (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988)

New Political historians from the 1970s are not generally the subjects of most Early American Republic graduate seminar courses. In many ways, their focus on the politics of the masses has been left behind. However, from their research can come valuable insights and narratives that challenge the way we think about the growth of democracy in the Antebellum era. Paul Goodman (1934-1995), a professor of history at the University of California Davis, was one of the pioneers in the field who challenged traditional narratives of the early Antebellum period.

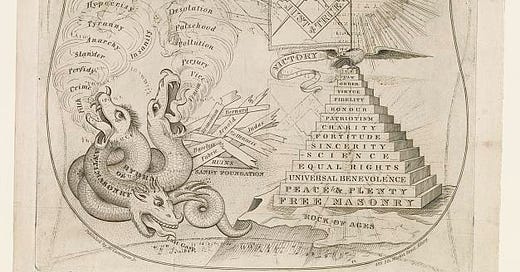

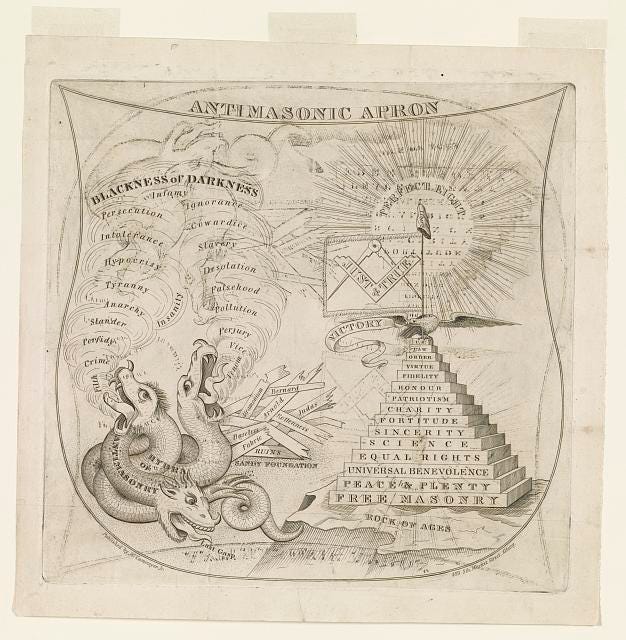

In Towards a Christian Republic (1988), Goodman takes seriously the anti-masons (those opposed to Free Masonry) as a force in American life and looks at the development of the movement from the mid-1820s through the 1830s when they were absorbed primarily by the Whig party. Drawing from large swaths of political data, Goodman situates the anti-masonic party as a middle-class, evangelical, and “in-between” generation of activists who saw in Masonry the ills of a developing industrial society that broke societal bonds and stratified classes. The attacks on Free Masonry, grew out of a single case of a man disappearing for revealing masonic rites, but ultimately became a movement that helped build the Whig coalition into a national party.

Goodman urges readers to note the insecurity felt by many anti-masons over the state of their world. Primarily a Northern movement, the anti-masons targeted Masonic lodges (which had exploded in popularity following the American Revolution) as secretive, undemocratic, and a cabal that had infiltrated all parties. The unwillingness of the National Republicans or the Jacksonian Democrats to initially back anti-masonry led to the development of a third-party that dramatically swung elections both at local, state, and national levels. In some states, the anti-masonic party dominated politics well into the 1830s. However, Free Masonry and anti-masonry in Goodman’s arguments were merely symptoms of a wider discontent with the rapidly changing social, economic, and political world of 1820s America.

Goodman is particularly strong in showing the connection between the strength of the anti-masonic party and how strong the two party system was in a state. In states like Massachusetts, where the two party system was in flux, anti-masons were able to develop a strong third party that swung elections. However, in states where the two party system was strong, such as Connecticut, the reform movement was already incorporated into major parties, thus breaking anti-masonry power.

Goodman does an excellent job in showing how anti-masonry was not merely a discontented rural movement, but rather drew from masonry and evangelical Christianity. This movement caused the collapse of Masonry throughout the United States and decimated the number of Masonic Lodges. I found it particularly fascinating that many reformers felt Masonry was a threat to the family and home because it took men away from their home responsibilities and their wives, thus depriving men of the feminine spaces that helped temper and moderate men. Ultimately however, Goodman notes that Masonry represented the growth of an exclusive upper class system that was resented by those who saw it as anti-egalitarian.

While this book is fascinating, there are some areas that felt weaker to me. For example, Goodman emphasizes that economics were the root cause of the conflict. However, this downplays theological and cultural ideas that were not necessarily tied to economics. Furthermore, in describing the Masons, Goodman often seems to rely more on their opponents’ or former members’ descriptions of the Order, an often less than accurate range of sources to draw from. Masonry is portrayed as largely secularizing and deistic, despite the fact that most American members were deeply religious. Furthermore, in Goodman’s narrative, there is a totalizing element that obscures the numerous non-rational elements of why people act in the way that they do. This is one of the biggest challenges with political history is attempting to make all decisions logical. Human beings often make decisions based on impulses, rather than deep, logical thought. This book lacks that element, thereby making the rise of anti-masonry lose some of the hysterical element that has fueled many “anti” movements throughout American history (Anti-Latter-day Saint movements being one example).

This was a fascinating book that took seriously the anti-masonic movement as a factor in driving the rise of the Whig party in the 1830s. While ultimately the anti-masons faded as a political force, many of the original crusaders continued the plethora of battles they began in the 1820s including antislavery and temperance activism, education reform and poverty relief. Goodman’s work is an excellent starting point in seeing the basis of a northern reform party and its transforming effects on the American political landscape.

Robert Swanson