Review of Chamber's "The American Party Systems." (1975)

Ed. William Nisbet Chambers and Walter Dean Burnham, The American Party Systems: Stages of Political Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), pgs. 374.

Written as part of the ascendency of the New Political History school in the United States, this edited collection of essays offers a view of how historians and political scientists worked together and drew on theories in political science to attempt to create explanations for the politics of the United States throughout its history. Dense and technical, this book has some ideas that are still useful to current scholarly debates, however, some flaws in the methodology make it less powerful than it could have been.

Edited by William Chambers and Walter Burnham, The American Party Systems is divided into eleven chapters that cover the broad swath of American history. Divided between five historians and five political scientists, both groups employ datasets and political science theories to make their arguments. Ultimately one of the largest arguments of the volume is the need for historians to look at the politics from a data driven and ground up approach. In order to do so, the authors turned to voting samples, election results, comparisons between election years, and other mass data results to frame their arguments.

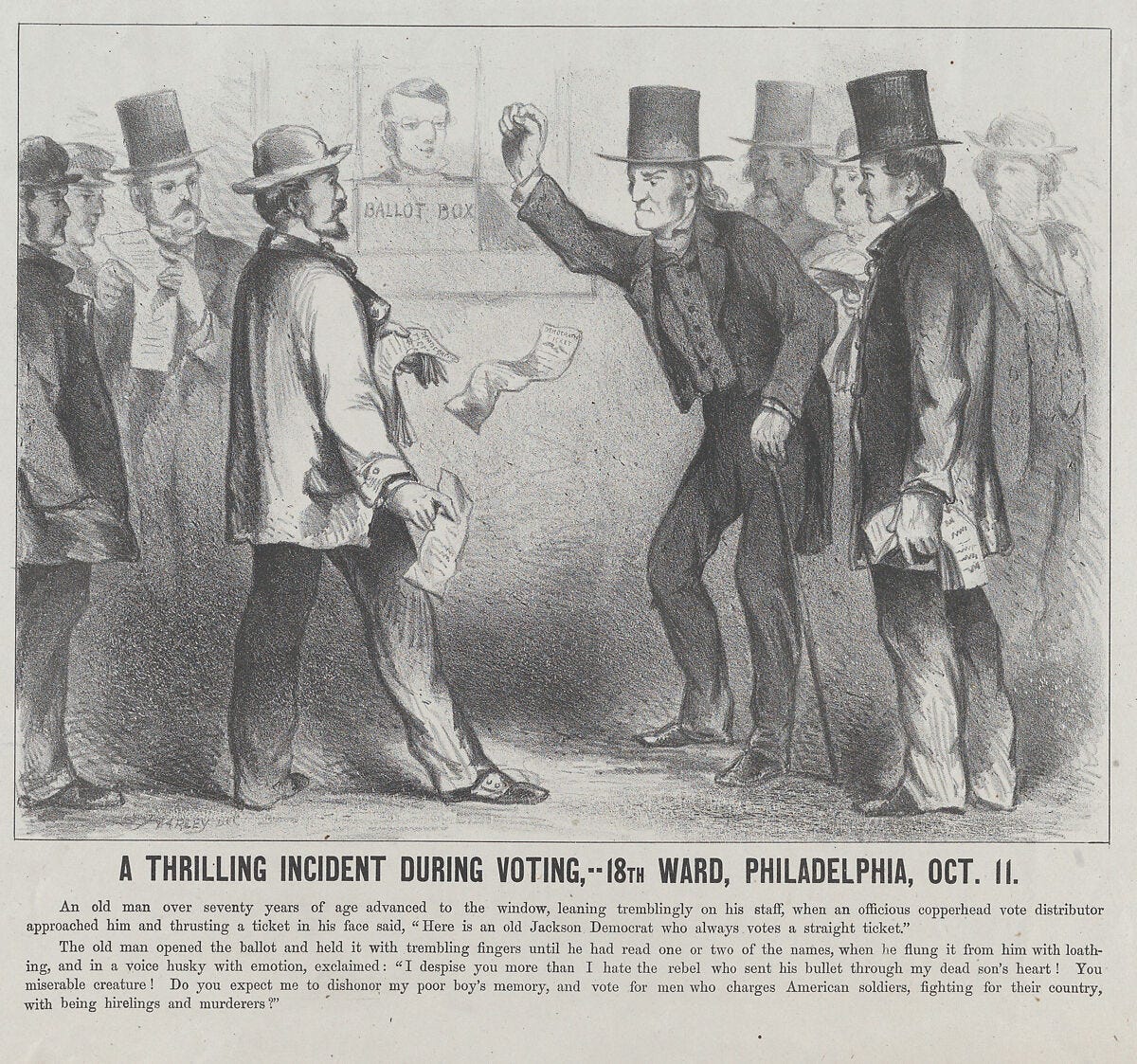

Several key points provide unique insight. For example Paul Durham emphasizes the need to consider the role of sectional and provincial loyalties when considering how the first party system (1790s to 1820s). I found it fascinating when exploring the next chapter by Richard P. McCormick, the role of “evangelical imperialism” in the drive to form a Democrat coalition. Not only did antislavery factor into elections, but many minorities (read Catholics, immigrants, and Latter-day Saints (though not mentioned in the text)) aligned with Democrats who were less anxious over their role in the American Republic than those within the Republican Party. I would note that today, this coalition is given less emphasis than slavery as a factor in in the buildup of the Democratic coalition. Finally, a fascinating article by Eric McKirtrick illustrates broadly how parties can help provide stability under the Constitution by comparing the Union and Confederate governments. The Republic Party in the 1860s helped shore up Lincoln’s government and prevent infighting to the extent seen in Jefferson Davis’s government.

Ultimately, the breadth and theoretical nature of this work are its biggest hindrances. Too often, the bird’s eye view obscures other issues such as slavery and hyper accentuates issues such as economics or broad mass categories that rarely capture the individual and local nuance. Furthermore, in attempting to find a theory that is applicable across time, much of the nuance of generational and cultural change is neglected. America is framed as in isolation, rather than in the vibrant transatlantic community it helped build.

Overall this was an harder read, but one that shows the growth of the efforts of historians to apply social science methods to develop theories of history. Ultimately, I remain unconvinced, but it was a useful exercise in exploring new ideas and theories.

Robert Swanson