Onward to Jerusalem - The Spanish African Empire

Review of article by Andrew W. Devereux, "North Africa in Early Modern Spanish Political Thought" (2012)

Andrew W. Devereux, “North Africa in Early Modern Spanish Political Thought,” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 12, no. 3 (Sep. 2012), 275-291.

When tourists pass through the streets of Barcelona or survey the ruins of castles scattered across modern Spain, few can picture a fractured Iberian world, controlled by an assortment of Muslim and Christian kingdoms arranged in a constant patchwork of shifting alliances. While religion mattered, in the medieval period Christian kingdoms and Muslim emirates were perfectly willing to align with each other against hated rivals. That is until the rise of Ferdinand and Isabella.

Plenty of histories detail the rise of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. Ferdinand and Isabella, motivated by a desire to expand and build a Christian empire that could recapture the Holy Land from Muslim powers united the two most powerful kingdoms in Iberia, then proceeded to incorporate other Christian and Muslim states at a rapid pace. Between 1482-1491, the two monarchs led a campaign to conquer the last hold out of Muslim control in Iberia (the Muslim conquest of Iberia had occurred several hundred years earlier). By the time that Christopher Columbus sailed west, the Muslim Kingdom of Granada was a memory and Spain (in reality a loose alliance between the Christian polities of Castile and Aragon) stood as the preeminent power in southern Europe.

Scholars have viewed this conquest as critical to the explosion of the Spanish empire across the globe. In the next hundred years, Spanish soldiers would establish imperial control throughout the islands of the Caribbean, large swaths of Central and South America, as well as outposts in Asia. Furthermore, with the rise of the Hapsburgs as monarchs of Spain, the empire incorporated large swaths of continental Europe. In less than a century, the Spanish had created a global empire that stood poised to dominate the Americas and Europe.

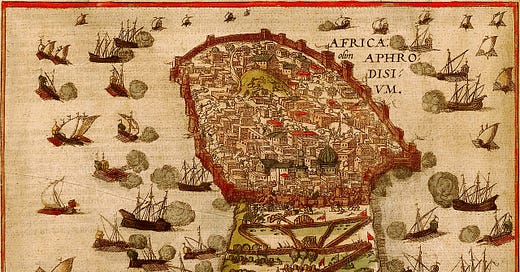

Andrew Devereux, an associate professor of history at the University of California San Diego agrees that the Spanish victories in Iberia heralded the rise of the Spanish empire. However, his essay pulls the reader away from the traditional locations of study of the Americas, the Low Countries, Italy, or even the Pacific Rim. Instead, Devereux directs his readers to see how between the 1480s and the 1580s Spain’s imperial leadership was focused on establishing territorial control across North Africa as far as Egypt. The ultimate goal was two fold, to control Mediterranean trade, but more importantly, to create a areas of control could support Spanish armies on their way towards the Holy Land.

This exploration of the efforts of Spanish armies to expand eastward towards Egypt and eventually Jerusalem highlights an aspect of Spanish imperialism that is frequently overlooked by many historians, that is the intensely millennialistic nature of the early Spanish empire. Seeing their recent military success in Iberia as evidence of their mission to secure Christianity’s holy sites in preparation for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, Ferdinand and Isabella directed their forces to begin seizing African territory, advancing as far as Tripoli in modern Libya.

Devereux does an excellent job of balancing revisionism while incorporating existing scholarship. He agrees with scholars that Spanish monarchs were interested in global expansion. However, he notes that that when reintegrating Africa into Spanish imperial history, it becomes clear that their vision of empire was far more religious and expansive than traditionally portrayed. This goal of conquering Africa remained on the table for decades until the rise of the Ottoman Empire shifted Spanish imperial focus towards Eastern Europe. By the 1580s, the African imperial experience had largely been abandoned as both Spain and the Ottoman empire entered an uneasy period of truce.

I found this essay fascinating both from a historiographical perspective and from its contribution to Spanish imperial studies. I believe one important element from this essay is showing how a myopic vision of the past can obscure the reality of what actually happened. Because scholars have largely emphasized the Spanish American empire, the millenialistic vision of Ferdinand and Isabella had been obscured. However, by reintegrating Spain’s African empire, the intense belief that the Millennium hinged on Spain’s control of Jerusalem can more fully be integrated into the narrative, challenging scholars to rethink how we describe Spain’s imperial expansion and the views of how Ferdinand and Isabella imagined themselves in history.

Robert Swanson