Latin American Republican Modernity, a Potential World Now Lost

A Review of Sander’s "The Vanguard of the Atlantic World" (2014)

James E. Sanders, The Vanguard of the Atlantic World: Creating Modernity, Nation, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century Latin America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

James Sanders, a historian of Latin American history at Utah State University, argues that scholars have myopically centered their attention on modernity originating out of Europe and have as a result missed the thirty year period in which Latin Americans created their own form of modernity, which he calls the “American republican culture of modernity.” Exploring the thirty year rise and decline of this form of modernity which was centered on universalism, abolitionism, republicanism, and the idea of civilization, Sanders engages with a host of scholars who he argues have obscured and oversimplified Latin America's contribution to the modern world and the development of ideas of republicanism and equality.

Sanders of necessity dives into the complexity of the term modernity, but he himself loosely defines it as a discourse in which people believe that they are modern. This more open definition allows Sanders to argue that there are multiple modernities. This further allows him the ability to place into comparison three sets of modernity throughout his book. These three, European monarchical/conservative modernity, Latin American republican modernity, and industrial (read North American) modernity each play essential roles in Sander’s narrative and in driving the formation of our modern world.

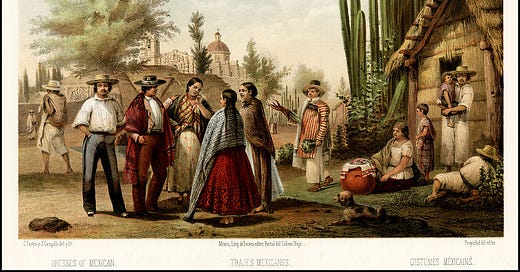

Latin American republican modernity is the central focus of this book. Initially stemming from ideas propagated during the Age of Revolutions, this form of modernity became key to Latin American liberals and “the pueblo” (i.e. the lower sorts) in the mid-1800s. Centered on a rejection of the “Old World” civilization and on the promotion of equality and political based “civilization,” this modernity first began taking shape in the early 1840s as Uruguayan liberals (both creole and Europeans) argued that their conflict with conservatives in Montevideo were really part of a larger Atlantic conflict between the forces of freedom and tyranny. Sanders tells the story of Latin American’s views of this Atlantic world conflict primarily through divides between liberal elites, the pueblo, and conservative elites in Mexico and Colombia.

Sanders ends by discussing the collapse of this form of modernity in the 1880s as American driven industrial modernity overwhelmed Latin Americans and led to the diminishment of racial equality and removal of subalterns from the political process. Latin Americans began to see themselves as examples for the rest of the Atlantic world and believed themselves to be the most “civilized” and modern states in the Western world. Whereas Latin Americans had previously seen the United States as a “sister republic,” by the 1880s the United States was seen as a hostile imperial power, similar to France and Great Britain. As Latin American elites felt that their nations fell behind, scientific racism, capitalism, and a lack of interest in political equality came to dominate the Western Hemisphere as American imperialists pushed and broke down barriers into Latin American states.

Overall, this is a fascinating book, however the text at presented the Latin American republics as far too idyllic. For example, numerous scholars have stressed the tense and unsettled nature of race relations in Latin America, yet these conflicts are only lightly touched upon. Sanders presents an almost Frank Tannenbaum like argument (which should be noted I believe still has merit in some regards). For Sanders, rather than religion and Roman legal law driving more harmonious race relations, it is the egalitarianism of Latin American republican modernity. While Sanders does mention moments of tension, they are fleeting and egalitarianism is emphasized to the point it obscures any divergence with this complex area.

Though not without its flaws, Sanders makes an interesting case to include the brief thirty year period between 1840-1870 as a period of development for a unique flavor of modernity coming out of Latin America. Latin Americans are presented as seeing themselves as the teachers of modernity to a world that was re-emphasizing hierarchy and which was increasingly founded on industrial power. However, whether the arguments of this book will have the staying power to become a primary method of explaining the post-revolution period in Latin America is yet to be seen.