Kevin Dawson, Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), pg. 360.

Kevin Dawson, an associate professor of history at the University of California, takes the reader into a world that far too often historians forget existed, the aquatic cultures of West Africa and those of people of African descent in the Americas. Dawson argues that a “constellation” of aquascapes, or aquatic cultures from Africa were transferred to the Americas by the slave trade.

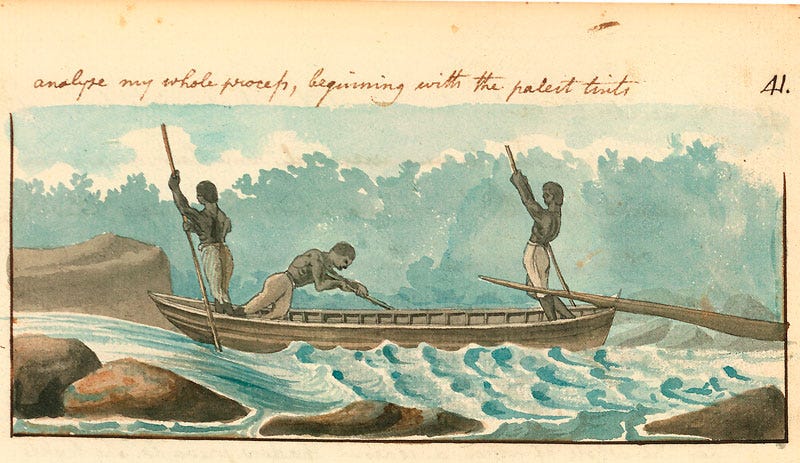

Dawson argues that European cultures largely had a healthy fear of the sea (despite using it as a means of conveyance) in the early modern era and that many African cultures’ embrace of the river and coastal waters led to a unique interaction between these distinctive groups. However, as the two cultures mingled and as Africans were transported as enslaved people across the Atlantic new forms of African influenced aquatic cultures developed. Insightfully, Dawson notes that Europeans quickly recognized and rewarded those people of African descent from African groups with experience with water culture (i.e. boating, shipping, etc.) by giving them slightly more freedom than other enslaved people. These African people, though still enslaved, were given greater freedom and influenced American culture with objects such as the dug out canoe (traditionally argued to be the creation of Native Americans) and with helping in industries such as the pearl industry or transportation industry. These in turn led to increased profits for their enslavers and generated increased local profits.

Dawson’s argument, that the water cultures of Africa were influential in the Americas was intriguing. However, there were some aspects of his book that were less convincing. At times it felt as if the author did not trace change over time with precision, at times comparing cultures across centuries of time. Furthermore, Dawson is not as careful to distinguish between the varied African cultures, seeming to suggest that there was such as hegemonic culture as “Africans.” While stating that there was a host of various cultures, this was not always clearly shown. Finally, too often Dawson neglects the role that interior trade routes had in bringing many of the enslaved people from West African coast for trade. Many of those brought to market were clearly not aquatic culture based, making statements such as we “cannot regard enslaved Africans as land people” (Ch. 7) less than accurate.

Overall, this was an interesting book, though one with some deficiencies that will require revision and fine tuning. The idea that river systems played a key role in African commerce, warfare, and in exchanging ideas is important. For Atlantic scholars, Dawson’s success in tracing some of these cultures and traditions across the Atlantic lends more to the idea that while brutal, the Middle Passage was not as cultural suffocating as some scholars have suggested. Rather, African pasts lingered in the waterways across the United States and other regions of the Americas.

Robert Swanson