A Toast and a Parade! Finding American Nationalism's Origins

A Review of David Waldstreicher's "In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes," (1997)

David Waldstreicher, In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776-1820 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), pgs. 384.

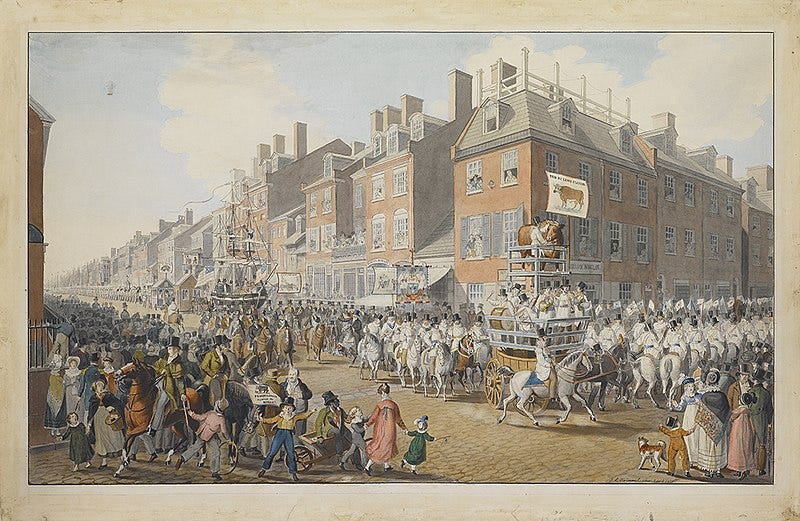

Many might recognize David Waldstreicher, a professor of history at the City University of New York and one of the first to contribute to the New New Political history style (the blending of cultural and political history), for his popular work Slavery’s Constitution (2009), however some the themes and ideas presented in that work, of a national consensus built on excluding people of African decent from the national project, were exhibited in his first book In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776-1820 (1997). However, this early monograph is far more than simply about race in the early American Republic. Rather, it is a book that highlights the role of public celebrations such as parades, victory speeches, toasts, and newspaper articles in building a new nationalism through the “relentless politicization” of American culture. It was in the political contests of the new nation that the symbols and ideas surrounding what it means to be American were born.

Waldstreicher follows a chronological methodology in which he begins in the colonial period and continues through to the 1830s. Divided into six chapters with an introduction and conclusion, his book has a good amount of theory that connects his work to others scholars discussions of nationalism, race, and gender. In expanding the realm of politics beyond the ballot box (one of the significant contributions of the New New Political historians) Waldstreicher shows that women and minorities also embraced the politics of nationalism, though they sought to modify and change aspects of the new national culture which subjugated them.

One of the strengths of Waldstreicher’s book is showing that through ordinary events such as parades and toasts, we can see the politics of both elites and lower sorts, a truly national culture. What he finds in these political events is long standing dual between groups in the colonies and then the United States. In the 1770s, it was the American Whigs versus the Tories and Parliament, in the 1780s, the conflicts centered around Federalists and Anti-Federalists. The 1790s-1810s witnessed heavy political confrontation between federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans. And in the 1820s, the confrontation between abolitionists and the South/colonizationists lead to a dialectic culture in which the actions of one group influences the other. For example, during the debates over the Constitution, anti-Federalists shifted the terms of the debate by emphasizing a Bill of Rights. Abolitionists, particularly Black abolitionists’ confrontations with slavery helped spur the growth of a Southern sectionalism. In each period observed, the push and pull of the major political factions (Whig/Tory, Federalist/Anti-Federalist, Federalist/Jeffersonian Republican, Abolitionist/Slaveholder) profoundly influences parades, speeches, and public rituals in which these conflicts are brought into the public realm. Essentially, Americans drew from the British tradition of having both a government and an opposition that rallied to the people to their causes. Importantly, Waldstreicher shows that the creation of a new nation was hardly just the work of elites. Rather, a broad American nationalism (though what that meant was contested by either side of the political divide) drew strength from the masses and public support. Throughout the book Waldstreicher does a fantastic job of probing the meaning of simple events such as a toast to find the deeper contests of power in the early Republic.

The mass of evidence that Waldstreicher brings together is impressive and much of his argument has significant merit. However, there are areas that are not as strong. Waldstreicher does well at incorporating the works of those engaged in the study of nationalism, however, the insertion of jargony language and abstract ideas of nationalism slows down and at times completely interrupts the flow of the book. Furthermore, Waldstreicher as in some of his other books (notably Slavery’s Constitution) steps into describing past decision-making and events that are not as clear via the documentation with a great deal more conjecture and much more certainty than I think the evidence warrants. For example, in Chapter 1 when describing the patriots Fourth of July celebrations Waldstreicher asserts with far too much certainty, that the reason patriot descriptions of the Fourth of July celebrations during the war were brief was to deemphasize regionalism and instead emphasize nationalism. This is despite the fact that other possibilities could very well exist and he cites no certain evidence for his conclusions that make those other possibilities not impossible, and far more likely than a cross continental coordination movement to not talk about the celebrations in any way that didn’t emphasize the growing American nationalism.

Another area that could have been explored more is coalition making in British North America and then the United States. Far too often political factions are framed as being united, which many were. However, this downplays the compromises and sacrifices necessary to hold the coalitions together. For example, when Waldstreicher examines toasts, he early on notes that these toasts often were a subject of debate as people argued over which lines to include or reject. It is in the debates that we see a broader, sweeping, and conflicted coalition coming together, however he does not particularly see these as evidence of a divided populace, but rather of a unified culture. Rather than the toast being a symbol of a united front, it should be seen as the conglomeration of multiple groups, each trying to incorporate themselves into the broader political whole. This is no where more evident than in his framing of the American colonization movement in which he frames the movement as largely united in creating a white republic (though scholars like Beverly Tomek have shown it was more complicated than that). Another area this is lacking is when he shows the East-West conflict in the early republic. He fails to show that the West was highly fractured as well, with each region being colonized by different sectional cultures.

A final note is that this book is largely a book about the cultures north of Virginia. Waldstreicher offers a national narrative, but his evidence is mostly from the cities of the North or Virginia, which is perhaps why the sectional divide comes so late in his work.

In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes is a fascinating and well-research book. It is not the easiest read, but for scholars of the Early Republic, it is essential. Waldstreicher demonstrates persuasively that a mass, national culture was growing in the United States and that it was only through conflict between different regions and people that the identity of what it means to be American was created.

Robert Swanson

Please feel free to ask questions or comment below!