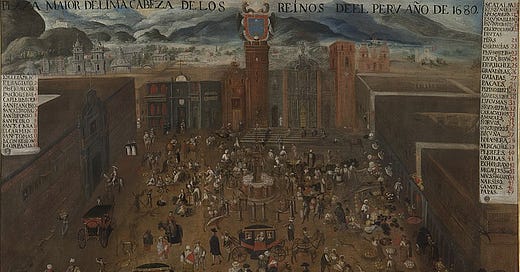

A Panoramic View of a Indigenous Revolution

A Review of Serulnikov's "Revolution in the Andes." (2013)

Sergio Serulnikov, Revolution in the Andes: The Age of Túpac Amaru (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), pgs. 184.

Sergio Serulnikov, a professor of history at the Universidad de San Andres , Buenos Aires, Argentina, first published his book Revolution in the Andres: The Era of Túpac Amaru (2010 Spanish, 2013 English) to scholarly acclaim. A synthesis of existing scholarship on the Túpac Amaru revolts that occurred in the 1780s in what is now Peru and Bolivia, his book was called “a concise survey” that brings “clarity to a complex group of uprisings,” an “excellent overview,” and a “fresh, although brief panorama.”1 From an outsider perspective, this book is well written and captures one of the largest Indigenous rebellions against Spanish rule in the empire’s history. Serulnikov brings together political, micro, subaltern, and postcolonial histories into a single volume without compromising a basic narrative structure. Importantly, in tracing the progress and collapse of the revolt, Serulnikov breaks free from nationalist and revolutionary tropes that have often surrounded the revolt, instead placing it in the context of local conditions and a broader Spanish imperial culture.

Composed of seventeen chapters, this book is in reality a much slimmer volume than the quantity of chapters implies. At only one hundred and eighty-four pages, Revolution in the Andes nevertheless delivers a cohesive narrative centered on the revolting Andeans’ idea that “the government of the Andes should be restored to the lands' ancient owners.”2 However, this focus does not imply that the process of revolt was initially radical. In fact, in some of the locales where uprisings occurred, it was actually seen as part of a larger process of restoring rights that Indigenous and creole populations believed they were entitled to. Yet, by the end of the revolt the uprising had clearly become anticolonial with violent fighting targeting all Europeans, Creoles, and Catholic officials. Tracing how and why this transition occurred is at the heart of the book.

From the start Serulnikov argues that the start of the rebellion was not “spontaneous or unforeseen.”3 Rather than a random uprising of oppressed masses, this was a movement guided by charismatic leaders including Túpac Amaru II, Tomás Katari, and Túpac Katari that channeled indigenous resentment against the oppression of lower level officials and worsening economic conditions that had created dramatic hardship in the lives of the lowest level of indigenous peasants. Initially, these leaders situated their revolts as protests within the Spanish empire. Rather than overthrow the empire itself, leaders such as Tomás Katari looked to carve out a space within Spanish control where native peoples had greater control of the levers of power at the local and regional levels. This distinction is incredibly important as it places the revolt with the concept of established order, rather than as a revolutionary action. Amaru II and Tomás Katari, the initial actors in this narrative, both worked within the colonial system and in some cases had won additional protections for indigenous peoples from their respective viceroyalties. It was only after the refusal of local officials to concede power that the revolts took on an increasingly radical nature. By the time that Túpac Katari, a non-elite peasant leader, entered the political stage, the revolt had become increasingly radical and markedly more violent. As the revolt turned towards revolution, creoles increasingly moved away from the native position due to the threats that it posed to their status in society.

There are some areas where Revolution in the Andes is far weaker. For example, the role of religion is largely neglected throughout the book until Chapter Ten when suddenly the followers of Túpac turn on the Catholic church as a result of its continued support of the colonial structure. Serulnikov frames this as a final break with the colonial regime and a transition towards a full revolution. Inherently then, the Catholic church is merely another means of colonial authority (which is not necessarily wrong). However, what additional insights could be gained by exploring the theological underpinnings of this break? What transformed the theological understandings of the rebels so that the break with Catholicism was possible? As Serulnikov notes repeatedly, the Andean peoples saw themselves as good Catholics, though they practiced it in their own way. Yet, the destruction of Catholic churches is more than just violence or an attack on political institutions. It constitutes a rupture in the theological foundations of imperial society, an attack directed at the holiest site in local communities. Could this underlying opposition to the church have played into why some did not join the uprising (as he notes not all Andeans followed Túpac Amura II)? This unexplored dimension of the revolt perhaps could be another productive avenue of inquiry in understanding how the revolt moved from protest to anticolonial.

Revolution in the Andes captures the nuance and complexity of the largest Andean revolt against Spanish colonial rule. Similar to other readers, I agree that this volume is both well-written and panoramic, providing both scholars and students a place to begin in their explorations of this crucial event. While more research will need to be done to capture underexplored aspects of the revolt, this provides a solid foundation upon which to build.

Robert Swanson